TONY LABAT

San Francisco, February 19, 2014

The following is an abbreviated conversation with Cuban-born and San Francisco-based artist Tony Labat on his approach to performance and documentation, and the 1970s Bay Area art scene. The information shared and context provided by Tony in this interview became invaluable primary source material for for my master's thesis "Matrix of Complex Relationships: David Ireland's 500 Capp Street" (California College of Art, 2014). The original conversation was recorded and took place at Atlas Cafe in San Francisco on February 19, 2014.

|

LAUREN

|

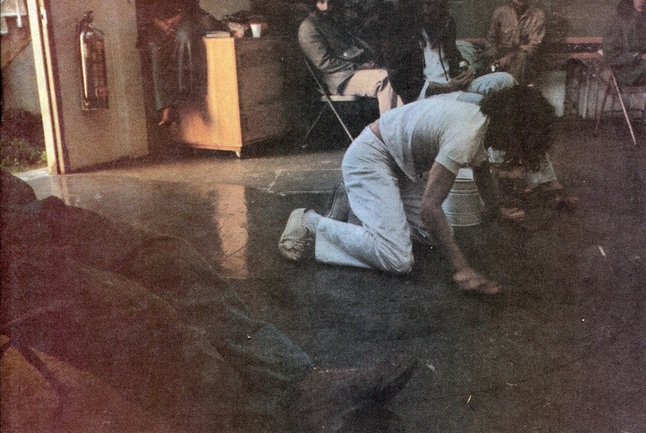

In the archive at 500 Capp Street, I found pictures of you videotaping David Ireland in the process of working on his house, what he calls maintenance actions. The images are documents of you recording Ireland cleaning his house, while simultaneously making your own artwork. In these moments there is a layering of documentation, process, performance, and art. Then recently, I also saw your interview in San Francisco Arts Quarterly (SFAQ) with the picture of your first performance in Studio 9 for a class with Howard Fried at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) in 1977, in which you are also cleaning. Can you tell me more about performing an ordinary task, such as cleaning, and how it relates to ritual, as well as its greater symbolic meaning?

|

|

TONY

|

That’s interesting. I never connected those things you just pointed out…I mean this is a coincidence that I made this performance at the same time as I was videotaping David. Maybe that’s why I was perfect for the assignment of documenting him because I understood what he was doing. It’s interesting that you are connecting my performance to David’s activity of cleaning and cleansing.

|

|

Can you tell me more about your performance?

|

|

I arrived at SFAI in the fall of 1976 and Howard didn’t have Studio 9 as of yet, so we were having class in a closet size room with no windows between the sculpture and painting areas—it was this in between room in a hallway, which was perfect. [laughter] So that lasted for a semester and then in 1977, Howard’s class moved to Studio 9, which was the beginning of what became the performance video department and later the new genres department.

|

|

Which you are now the head of at SFAI? [1]

|

|

Well there are no more departmental chairs. There is now only a BFA chair and an MFA chair. I am the MFA chair of the whole graduate program. I am trying to turn it into a new genres program, if they let me. [laughter]

Ok, let me get back to the story of my performance…I had I just come from Miami where I spent 10 years, but my formative years were in Cuba during the revolution, I was there until 1966. So I brought with me a lot of baggage and that kind of exile community that I was trying to escape from. So what I brought with me was this sort of things from Santería, from Caribbean culture. A lot of rituals, a lot of superstitions…we could go into detail, but for now I think you get my drift. I was looking for a language. I didn’t know what to say or how to say it or where to speak. By appropriating this kind of ritual, it was this idea of cleansing the space that you are going to work, live, and spend time in. It was this kind of combination as we moved into Studio 9, that my first performance, moving in the class there, was to do this sort of cleansing as you will. It involved rum, cigar smoke, and then throwing a bucket of dirty water out the door. |

|

How did you incorporate the rum and cigar smoke into the performance?

|

|

I sort of sprayed the rum with my mouth into the corners of the room and I inverted the cigar into my mouth, like the hippies used to do with joints, and then I blew smoke out into the space—kind of like Cuban Feng Shui. [laughter] Making sure that things were in place and that the bad stuff was out—a clean slate, a clean palette

|

|

So not only cleaning the dirt off the floor, but also cleaning any sort of bad energy from the space, a spiritual cleansing.

|

|

Yes. And setting up the space for the rest of the community.

|

|

That’s a really nice gesture.

|

|

I was dressed in all white, which is another reference to Santería, but I don’t practice that religion.

|

|

So you used these religious rituals as a reference to your formative years in Cuba?

|

|

It was very formal. How could I use these things that are so powerful. I was curious to see if I could translate the power of the rituals that I experienced, heard about, and read about into a very formal set. I wanted to see if as long as I believed in that moment, that the rituals would work. I was trying to take the ceremonial language out of context

|

|

I like that earlier you used the word appropriation.

|

|

Yes, I was appropriating the religious rituals for my own rituals within the art context.

|

|

This performance was photographed, but was it also videotaped?

|

|

No. I never videotaped performances. I always hated that. For me there was a romance in the work of the artists that were influencing me. The information I was getting in Miami before I came to SFAI was mostly stills of performances with descriptions. My own preference was to give priority to the image of the performance—that frozen moment—because otherwise you would have to be there.

|

|

So the image is the only documentation of the performance?

|

|

In this case, it is purely a document, because this piece was about an hour long so there were constant photographs. It was a durational piece. I may go through the mud, but it is always to arrive at one image, which might take 45 minutes. I prefer the stills.

|

|

In your own performances, you do not videotape them and only take photographs, but you did videotape David Ireland’s process at 500 Capp Street.

|

|

[laughter] Yeah.

|

|

This situation was different. In this case, you are the video artist rather than the performer. Did you see yourself also as a performer in David Ireland’s work?

|

|

I think David and I were both making sculpture and we understood that without saying anything about it. It is interesting that you bring this up. I think there was a mutual enthusiasm. We hit it off right away; there was chemistry between David and me.

|

|

Because of the house?

|

|

Yes.

|

|

He invited you there?

|

|

This was a long time ago, so I will do my best, but there are things that you don’t forget. David was looking for someone to document his process and Helene Fried (Howard Fried’s wife) sent me there to meet him. I walked into the house and there was still wallpaper on the walls. It was a house. David did not tell me much, simply what he was about to do, that he was going to do these actions, maintenance activities like stripping the molding off the windows, sanding the floors, ripping the wallpaper off. I went, “Ok, cool. When are you starting? Monday? I will see you Monday.”

|

|

And you were excited about capturing those activities on video?

|

|

I had no idea what I was getting myself into. I was just excited to have met him. At the time, I was also working at Tom Marioni’s Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA). I was a student and was encouraged by Howard to have experiences outside of SFAI. So when these opportunities came, I went for them. I was an apprentice to Tom Marioni, as he called it. I remember it as the janitor. [laughter] I was doing these activities over at MOCA, things like fixing leaks in the roof, but in a kind of sculptural way with whatever material was around. I was cleaning sinks and absurd things that were not working anymore. Just looking at them as objects. It’s really funny because you are bringing things up I never really connected. So then to go to David’s made sense. What I think David and I shared were a couple of things and one was the sculptural aspect of it…we were making sculpture.

|

|

What did you consider sculpture? Is the video you made of Ireland’s performance sculpture?

|

|

Well, the video was not going to be a documentary. It was not going to be linear. Well, it was linear in terms of the steps of taking the molding off first and then the sanding of the floor, but we never talked in the video. David never said a word, there was no interview, and I did not use documentary conventions. There is none of that. So we both thought about what was important, going back to sculpture, it was the sounds of working. Maybe I went a little overboard with the close ups, but I was making my own video work at the time. I was already very much into a certain kind of framing and this idea of sculpture as video…what is it communicating? To me it was the very aggressive sounds or the soothing ones; they had a range of different tones. Whether he was sanding [sanding noises] with the sandpaper on the wall or the aggressiveness of the molding coming off. Then there were very quiet moments, like washing the windows. So the sound was very important and that was one thing that we shared. He wanted close ups and I wanted close ups. So I showed up at his house and this went on for a few months.

|

|

In 1977?

|

|

1977. Yeah. I don’t remember exactly, but it was at least 6 or 8 months. I would come whenever he was about to start and he would say, “Ok, you got some footage of sanding. Wednesday I am going to do the molding.” So we would have a kind of script or schedule. From the first day we didn’t say a word until I turned the camera off at the end of the day. He wouldn’t say anything to me; he would just open the door and get back to what he was doing. It was kind of like sports journalism. There was no conversation about what he was going to be doing so I could start some shots—it was really on the fly. That’s why the video camera was hand held. My best analogy is like shooting sports. I had to go with the action.

|

|

This lack of communication is interesting. You mention that you had a script or schedule, but the lack of dialogue between you two allowed David to keep the authorship of his actions and you in control of how it was captured on video.

|

|

Yes. From the beginning what I really appreciated, was that I had this impression that he had his job and I had my job. I think in retrospect that he trusted me. There was a trust. I know that when the piece was done—I was nervous to show him the final cut—of course there were things that he was not in agreement with.

|

|

Did he let you make the decisions on what was included in the video?

|

|

Oh yeah. At times, a la David, he would make some joke like, “You really went close up on that one, didn’t you?” [laughter] or “I love the sound, give me more.” But I didn’t. I made three tapes: David Ireland’s House (1977, 19:28 minutes), David Ireland’s House Outside (1977), and Lunch with Mr. Gordon (1977). And later on I did one more tape for the Oakland Museum’s exhibition…that is the sad one. I made another video of David in the house in 1988. I was doing video portraits for SHIFT 7 magazine. The two that are my favorite are George Kuchar and David Ireland. With David, we started with him taking a shower and he takes me through a tour of all his objects, doing very eroticized actions all through the house without saying a word. That tape I really love too.

|

|

In an interview with David Ireland, he talks about your tape Lunch with Mr. Gordon.[2] He mentions a phrase that Mr. Gordon said . . .

|

|

“One donut is enough.”

|

|

Yes, and that it became a phrase you both would say to each other. It is interesting that although you didn’t talk to each other during the videotaping, you both shared the same moment—a bond created over these times spent together.

|

|

Oh, absolutely. We were incredibly close.

|

|

Do you consider Ireland’s work as a sort of performance?

|

|

Of course, with the quotidian as a private stage, so performance, of course, but his performance was not aimed at a live audience, he had a task at hand. From my point of view and from David’s, it was definitely a performance. There is a whole conversation around the idea that we don’t act the same when a camera is turned on. Is it possible to be yourself? So it is interesting now that you are bringing things up that I hadn’t thought about. But by his bringing in a camera, I think he was already set in a frame of making for others. At the time, what influenced me so much were the works of Bruce Nauman, Howard Fried, and Paul Kos. I came out of this post-studio moment and the idea of things happening in the studio. Like in Nauman’s tapes, we only see this moment in the studio because we have the videos. It’s kind of like reportage. So in the same sense, it was very normal to be documenting, shooting a video of what David was doing because we wanted to show the process to others, like you…so you can see it. The photos that I have seen are just too beautiful—the color and the drama—they look a little too commercial. It is a nice contrast to have the video. That early recording equipment was a drag; I had about sixty pounds on my shoulder with that old Porta-Pack. The footage was nitty-gritty, black and white, and raw. I like that because of what he was doing, for me, it was down and dirty. I don’t think the video romanticizes Ireland’s work—it is what it is.

|

|

You mention the romantic idea of not videotaping a performance in order for it to be an experienced event. For the videotape of Ireland’s performance, in a private setting with only the two of you present, where then does the audience come in? How do they experience Ireland’s process

|

|

In relation to the videos I made?

|

|

Yes, and in relation to the notion of performance, which by definition requires an audience.

|

|

Hmmm, that’s a good question. Let me see if this makes sense. David finishes the house and then there is the unveiling if you will, you have probably seen the poster. I think for that event, we met at the house first and then the group moved over to an Irish bar that used to be in the Mission with a beautiful horseshoe bar top. In the bar, I played the video while people ate and drank. So that event happened. Then I really felt like my tape was done, my job was over. The video was an archive, it was a document, and I knew that it was going to be really important. But because of that, maybe I wanted to respect…I don’t know what I wanted. I didn’t think that I was going to show that video. It’s not like I was going to hustle it and pass it around. The video is demanding, it is difficult, it’s rough, it’s tough, and it’s punk. [laughter] Plus I had my video work, so I wanted to be careful. So if David wanted to show the tape, I have it. If anyone wanted to see the tape, I have it. But I thought my job was done. I felt it was more of a relic, an archive, and a document.

|

|

What about the photographs taken?

|

|

I never talked to the photographer. Once in awhile I saw this guy, he would take pictures and then leave, that was about it.

|

|

Let’s get back to the videos.

|

|

Like I was saying, I don’t think those videos have been shown for twenty or thirty years. David went on to 65 Capp Street house and the museum/gallery context. So when all of that started to happen the tape went with 500 Capp Street. I don’t think I showed that tape again until his retrospective at Oakland Museum of California. Lunch with Mr. Gordon and David Ireland’s House Outside have never been shown.

|

|

Really?

|

|

Yeah. That is why they are so special.

|

|

You have a relationship with Ireland, but also with the house at 500 Capp Street. The video becomes a documentation of Ireland’s process, but also becomes something of a personal relic for you, as well as an artwork. Even if the video is not exhibited, its importance is something more personal than an artwork.

|

|

Oh yeah. That video makes me cry. I was at a point in my life and career where everything was exploding—what I knew, leaving Miami. It was also a moment of transformation for me. Hanging out with David at 500 Capp Street, with Tom at MOCA, and Howard in Studio 9 has always symbolized that moment for me. I was lucky and privileged; I got to San Francisco at the right time—for my trajectory.

|

|

I spoke with several people, including Tom Marioni, Paul Kos, and Connie Lewallen, about where David was within the lineage of Bay Area Conceptualism (BAC). It seems that he was kind of in between—he came after BAC, but also not really part of the second generation. That is he was floating in between.

|

|

I think that is what we had in common because I was in between, as well. David and I were both in between. There was something he was beginning, there was something in transition, and there was something he was leaving behind to embark on this incredible project, and so was I.

|

|

You both take on new meaning for your genres, taking the artwork further to a point of contextual examination.

|

|

[1] In 2020, San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), where Tony received his BFA (1978) and MFA (1980) and taught since 1985, ceased its degree programs and graduated its last class in 2022. [2] See Suzanne B. Riess, Inside 500 Capp Street: an oral history of David Ireland’s house (Berkeley: Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, 2003). |

|

Tony Labat is a San Francisco-based artist and MFA Chair at the San Francisco Art Insittute. Labat was born in Cuba and came to the United States at the age of 15 in 1966. He has exhibited internationally over the past 30 years. He has received numerous awards and grants and his work is in many private and public collections. Labat has developed a body of work in performance, video, sculpture, and installation. His work deals with the investigation of body, popular culture, identity, urban relations, politics, and the media.

|