INTERMEDIARY SPACE

Locating formal relationships in Field Conditions

A bird glides on the currents of the wind. The bird is not alone, but is with a flock of starlings that moves as one mass in the sky. The flock dissipates one moment and then at another swarms and collects into magnificent shapes. Watching their kinetic, unpredictable movements from afar, it is hard to tell that this surging and swelling form is in fact thousands of small birds. Still-images of this event cannot express the moments between each rise and fall of the swarm. This natural phenomenon—a starling murmuration—contains relationships between the bird and flock, the micro and macro, and the visible and invisible forces within the seemingly endless field of the sky.[1]

Field Conditions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) looks at these same relationships in works by artists and architects who explore imagined space through their varied practices—e.g., conceptual art, printmaking, drawing, multimedia art, and installation, among others. Here, architects approach their practice from the theoretical realm, the early stage of imagining space before it is built in the environment, an approach that lends itself well to a concept of space that the exhibition proposes, namely the field. For Joseph Becker, who curated Field Conditions, “[t]he field[…]provides a framework in which[…]forces [of infinity, motion, and repetition] may play out, setting the stage for investigations into the construction, representation, and experience of space, both inhabited and imagined.”[2] The field acts as a plane that has no dimensions or boundaries, making it potentially endless. Placing objects within the plane—such as birds, people, or lines—form conditions by the way the objects move together and around one another. Therefore, field conditions, as theorist and architect Stan Allen contends in his essay “From Object to Field,” “imply the design of systems, of assemblages and paying attention to intervals, to the space between things.”[3] The artworks play within the field of the exhibition to consider a space between opposing forces, such as the visible and invisible, micro and macro, and finite and infinite. I can’t help but notice the curatorial choice to emphasis visual binaries in the layout of Field Conditions: all works are black and white, other than a blue glow emanating from a few TV monitors; conceptual, dematerialized artwork appears alongside highly material, tactile work; and flat two-dimensional work leads to an immersive installation. While the individual artworks explore the theory of field conditions, bringing them together within the gallery draws more attention to their formal differences than the relationship produced amidst them. Therefore, where can viewers find this space between?

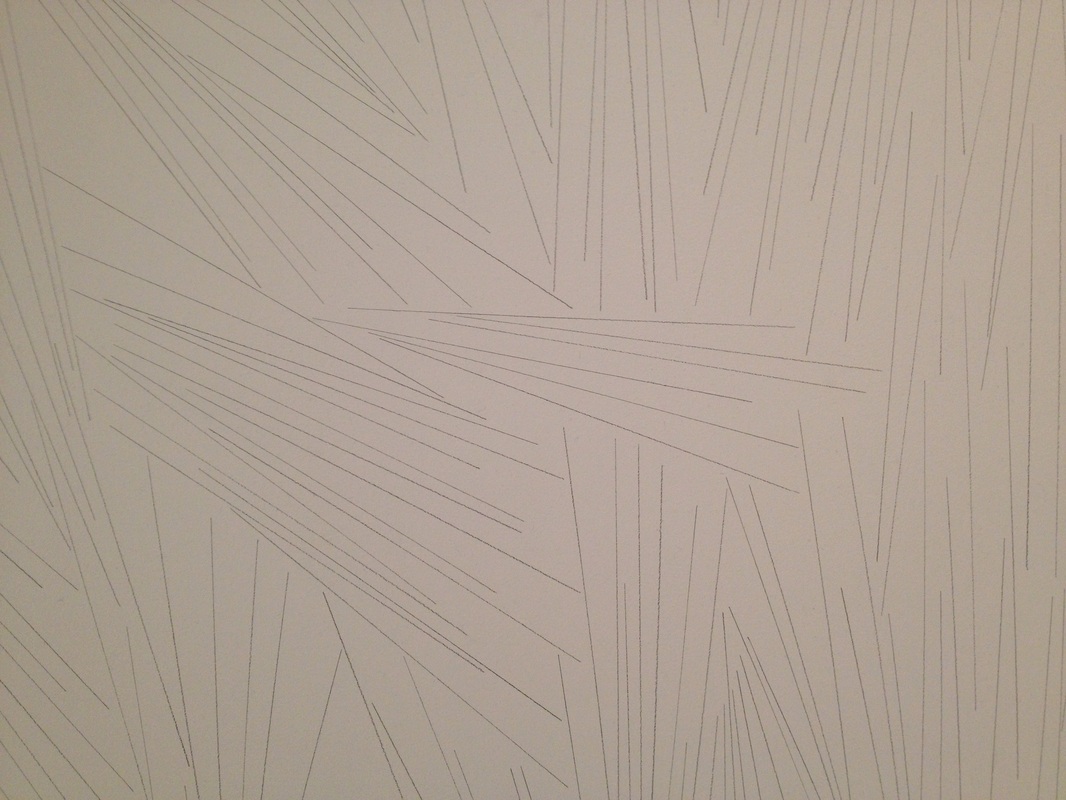

Across from Field Conditions’ introductory text, on a wall that leads into the first gallery is Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #45: Straight lines ten inches long, not touching, uniformly dispersed with maximum density, covering the entire surface of the wall (1970), which is a strong representation of the exhibition’s premise (see fig. 2). In this drawing, multiple clusters of ten-inch long lines fan out in various directions to fill the entire surface of the ten by thirty foot white wall. The thin graphite lines never touch or cross, but together create a uniform, yet spontaneous pattern. The simultaneous homogeneity and inconsistency of the pattern creates a contradictory visual effect of repetition and, at the same time, unexpected distinct moments. A close look at a small section reveals individual groupings of lines and their relationship to one another (see fig. 3). At a distance, the wall becomes a surface of light grey as the lines blur together. Moments of nearness and distance from the piece to contemplate the endless variables of patterns almost go unnoticed due to the placement of the artwork. The subtlety of the drawing, soft lighting, and the visitor’s path into the gallery leaves the work in a position where most visitors do not stop to see it until they are leaving. Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #45 does not attract the viewer based on its faint visual presence or placement, but its subtly provides a stronger emphasis on its conceptual ground in this exhibition.

LeWitt’s artwork is the instructions that he defines in the title, entrusting the act of drawing, in this case, to three installers approved by his estate. The only limits on the formation of Wall Drawing #45 are the instructions from the artist and the physical boundaries of the wall, whereas the arrangement of the lines is susceptible to change each time it is drawn. Therefore, LeWitt emphasizes the conceptual possibility of the artwork rather than the material product. Wall Drawing #45 is a good example of the binaries present in Field Conditions. When looking at the work from a distance, its light grey presence provides a literal middle ground between the black and white that overwhelms the rest of the exhibition. The drawing is a physical object in which the viewer can experience the various patterns of the lines within a framework, allowing a point of entry to the theoretical premise behind Field Conditions. While the drawing intends to be the introductory piece of the exhibition, the curator places the work outside of the galleries, both isolating it and demonstrating the way in which conceptual and material form can meet. This aforementioned isolation risks it not being approached until the end, if at all. Therefore, if the experience of the only connection between the poles of materiality and conceptuality is hindered, then how is the space between communicated in the rest of the exhibition?

|

(Figure 2) Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #45: Straight lines ten inches (25cm) long, not touching, uniformly dispersed with maximum density, covering the entire surface of the wall (detail), 1970. Graphite, dimensions variable. Collection of SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of Helen and Charles Schwab, 2000.439. Photo by author.

|

(Figure 3) Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #45: Straight lines ten inches (25cm) long, not touching, uniformly dispersed with maximum density, covering the entire surface of the wall (detail), 1970. Graphite, dimensions variable. Collection of SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of Helen and Charles Schwab, 2000.439. Photo by author.

|

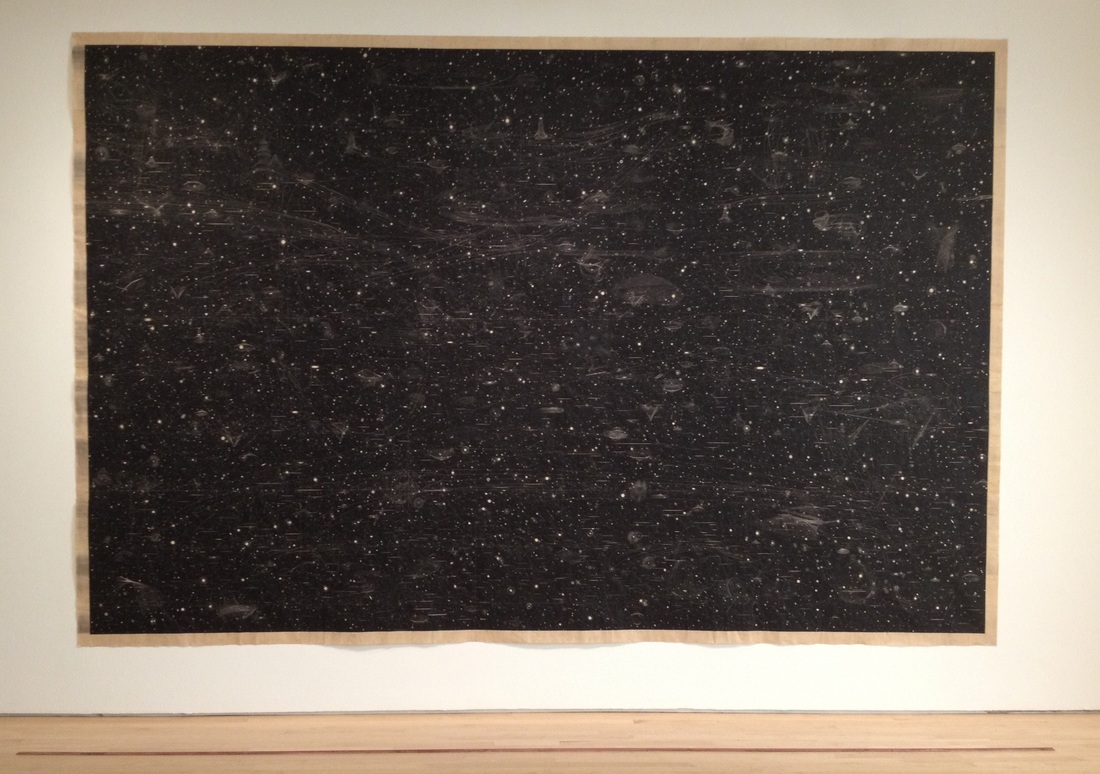

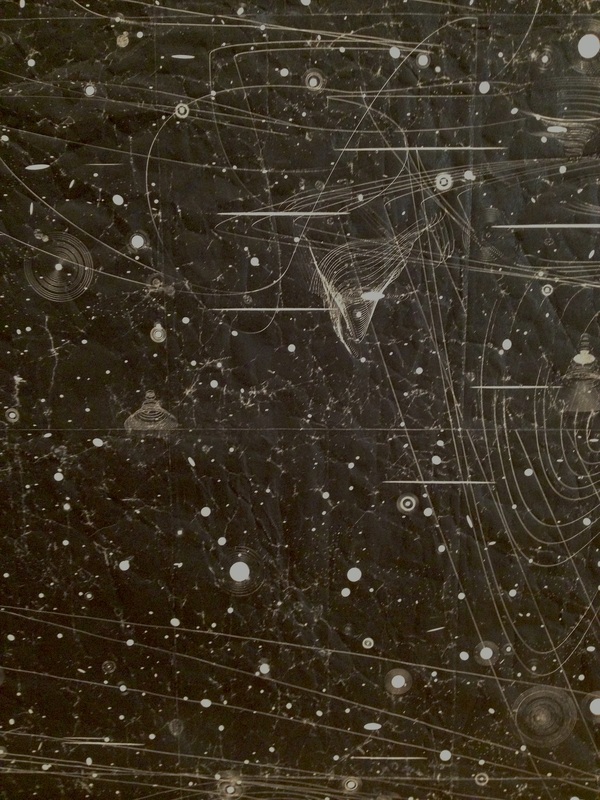

In contrast to LeWitt’s mostly conceptual artwork, Marsha Cottrell’s A Black Powder Rains Down Gently On My Sleepless Night (2012) relies heavily on its materiality (see fig. 4). In the first gallery of the exhibition, cater-cornered from LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #45, Cottrell’s print hangs by pushpins on its own wall. The artwork is a computer-generated image that is printed onto several sheets of thin, but strong mulberry paper. The black powder ink is applied using a printing method that uses electrostatic forces. The sheets are then gently seamed together to construct this large eight by twelve foot artwork. The interior borders of the sheets form a subtle grid over the piece, dissecting the curvilinear contours of the image (see fig. 5). The black represents the night’s sky, while delicate lines of creamy white form miniature universes and constellations. The swirling patterns run off the edge of the dark surface to disappear into the paper’s border, implying their continuation into a realm we cannot see. What is visible to the viewer almost immediately lures them in to inspect the soft texture of the black surface and tiny imaginary worlds. Cottrell purposefully creases the paper to generate intricate organic systems within its structure, which adds tactility and depth. At a distance, the crinkles form cloud-like sections of grey across the black powder sky.

Without the ability to navigate around the artwork, the viewer would not be able to discover the layering of the micro and macro in A Black Powder Rains Down Gently On My Sleepless Night. It is clear why this piece was chosen for the exhibition, however, it weighs heavily on the material side of the spectrum, whereas LeWitt’s work enables a conceptual experience through its materiality. Cottrell’s print facilitates the expansion of the delicate universe in the imagination of the viewer, however there is no conceptual framework to structure a system that produces both finite and infinite possibilities. Without the system, the viewer can imagine the infinite, but has no rules in which to locate the point of contrast in the finite. Therefore, A Black Powder Rains Down Gently On My Sleepless Night communicates only one extreme, rather than what can be found between the opposing forces.

|

(Figure 4) Marsha Cottrell, A Black Powder Rains Down Gently On My Sleepless Night, 2012. Iron oxide on mulberry paper, approximately 96 x 144 inches. Photo by author.

|

(Figure 5) Marsha Cottrell, A Black Powder Rains Down Gently On My Sleepless Night (detail), 2012. Iron oxide on mulberry paper, approximately 96 x 144 inches. Photo by author.

|

Leaving Cottrell’s print and the first softly lit gallery, the viewer enters the largest gallery in Field Conditions. The white walls of the rectangular room are empty. Two artworks are located in opposition to each other—one suspended from the ceiling and the other installed underfoot (see fig. 6). On the ceiling, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Homographies (2012) is four rows of white florescent tube lights that run the length of the gallery. When the gallery is empty of people, the florescent tubes are frozen in a repetitive pattern. As a viewer walks into the room and under Homographies, the bright light from above engulfs him/her and a slight hum of electricity and mechanical movement becomes audible. There is no visually activity until the viewer turns around and looks up. In response to the viewer, the tube lights rotate slowly behind him/her, tracing the wake of his/her path. The movement is reminiscent of a linear flow of water that follows the trail of a swimmer. However, in Homographies, there are no ripples to continue the motion and the rest of the gallery remains stagnant and flat. Lozano-Hemmer’s work does not focus on its conceptual or materiality qualities, but relies on the interactive experience of the viewer. The field of the gallery in which the viewer enters is flooded with florescent light and is absent of shadow, as a result, the space in which the viewer moves feels inactive, only drawing attention to the surface of things.

Below Lozano-Hemmer’s Homographies is Tauba Auerbach’s 50/50 Floor (2008/2012). Here two-inch ceramic tile squares, half black and half white, arbitrarily permeate the floor of the gallery. Their placement creates a stochastic sequence—a random pattern that may be analyzed statistically, but may not be predicted precisely.[4] Standing on the artwork and looking directly down onto the tiles, the viewer sees each perfect square attached to the other by grey grout. The grout suggests a middle ground—the physical location between two tiles but also the median color between black and white. Instinctively, the viewer tries to find figures in the monochrome pixilation. From afar, the pattern creates an undulating sea of black and white that is reminiscent of television static. However, it remains clearly black and white, unlike LeWitt’s drawing that from a distance creates a cohesive light grey. 50/50 Floor finds its depth not in the physical field, but closer to the conceptual tendencies of Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #45. Similar to LeWitt, Auerbach formed instructions for the artwork that require equal parts black and white tiles to be placed on the floor in a random pattern, which, in this exhibition, was done by hired installers and not the artist. The only restrictions are the dimensions of the tiles and the room in which they are installed, while the variation of patterns from the arrangement of black and white tiles is manifold. The main difference between LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #45 and Auerbach’s 50/50 Floor is the surface that they cover—respectively, the wall and the floor. These two architectural surfaces have different functions, especially in the gallery. The surface of the wall is to hang, or in this case, draw, artwork at the eye level of the viewer, whereas the floor is a surface for the viewer to move around the gallery. The floor, necessary to walk across and access other galleries, is about function, which draws attention away from the conceptual implications of the artwork.

|

(Figure 6) Installation view at SFMOMA. From top to bottom:

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Homographies, 2006. Fluorescent light tubes and custom tracking software, dimensions variable. Photo by author. Tauba Auerbach, 50/50 Floor, 2008/2012. Two-inch black and white ceramic tile and grout, dimensions variable. Photo by author. |

Homographies and 50/50 Floor compete for optical and experiential dominance: the light from the ceiling is so bright that it causes the tiles to reflect their pattern on the white walls, while the black and white floor draws the eyes down, distracting from the mechanical movement of the overhead lights. With both works requiring activation by the viewer, they negate one another. As a result, the physical space between the two artworks is an optical overload, which distracts from the premise of the exhibition—to consider the conditions that objects set on the expanded field, leading to intervals and relationships between extremes. Lozano-Hemmer and Auerbach’s artwork may be a chance for the viewer to physically enter the field, as described in the exhibitions concept, by its interactive and immersive qualities. However, the installations are the weakest point of connection between theory and the viewer’s experience due to the lack of subtlety and depth of the two works together—conceptually and materially.

Like the metaphor of the starling murmuration, the premise of Field Conditions is to explore the opposing forces of the macro and micro, visible and invisible, and finite and infinite within the framework of individual artworks. The variety of media and the complicated installations add to the ambitious nature of the exhibition. The placement of varied types of black and white artwork next to each other draws the viewer’s attention to the formal binaries and distracts from the deeper understanding of field conditions—which is not to point out the extremes, but to make relationships, intervals, and a space between things. In the same way ornithologists, physicists, and biologists study starling murmuration to learn about the relation of the bird to the flock and what it might tell us about human nature, Field Conditions’ premise can offer the viewer a better understanding of the field in which humans navigate. [5] However, one might wonder if the formal extremes of the monochrome artworks can communicate the finite and infinite gestures of the field into the viewer’s own vibrant world in which they live.

[1] Murmuration, as defined by the New Oxford American Dictionary, is the action of murmuring seen in rare flocking of starlings.

[2] Joseph Becker, Field Conditions, introductory text.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Stochastic as defined by the New Oxford American Dictionary.

[5] See Jonathan Rosen’s audio essay “Rome’s Starlings,” http://www.nytimes.com/packages/khtml/2007/04/22/magazine/20070422_BIRDS_FEATURE.html